The Meaning of Our Bars: A Chicago Perspective

Back in January I read about the closing of Irene’s Cabaret in Quincy, IL, after 36 years in business. When I saw the notice, my heart broke a little. I used to close that place several nights a week. Irene’s was where I sort of learned to hold my liquor and where I very publicly fell in, and out, of love. But most importantly, Irene’s Cabaret was where I learned that being gay was about more than having gay sex, it was also about being part of a community.

Our bars have been and always will be more than mere drinking establishments. In many ways they have been key components in the advancement of LGBT people.

LGBT enclaves and meeting spots have been documented as part of Chicago’s history since the early 1900s. But for my purposes, I’m going to fast forward to a little over 70 years ago, because it was with the influx of returning service-members after WWII that bar-centered LGBT socialization began to assume a more modern shape.

For many who served in the war, being far from home and in all-male or all-female living arrangements awakened feelings of desire. That new awareness, combined with a rise in urbanization, made things especially ripe for the emergence of a modern gay underground.

At the time being LGBT was illegal in the United States. Prior to 1973 homosexuality was classified by the American Psychiatric Association as a mental illness sometimes worthy of electroshock therapy and/or institutionalization to “protect” the general population.

Since our actual lives, as contributing members of society, were concealed by the need to remain closeted, it was easy to classify disembodied “queers” as perverts or subversives. Against this social backdrop, the flourishing of furtive “gay spaces” became cause for public concern, and pressure was placed on elected officials and law enforcement to suppress it. So going to gay bars, accepting a drink, and even dancing with a member of your own sex was done at a huge personal risk.

We were a threat because we knew the rules, but we broke them anyway. We were willing to risk being caught in periodic bar raids when the result might be having news of the scandalous arrest printed in the newspaper — which sometimes meant losing jobs, homes, and families. But our LGBT elders went to those bars anyway, because that reprieve from the everyday hiding they endured was worth the risk.

In gay bars people didn’t have to pretend. They were places of freedom in lives defined by repression. In those dim and mostly windowless taverns, LGBT people learned that the “lonely life” of the homosexual was a myth. They were not alone — they were members of a tribe of great size and diversity. With that connection to others, gay people came to realize that the problem wasn’t being gay, the problem was how being gay was perceived by society. Our bars helped to give us that self-awareness and “sense of community” – and from that sense of community, an actual community emerged.

At the time many LGBT bars were mafia run because “the mob” – with its connection to law enforcement – knew when raids were going to happen and had the cash needed to grease the right palms when necessary. Police department payoffs and police harassment were a routine reality of gay bars of the time.

Undercover cops were sent to try and get a patron to hit on them. When that happened the charge was lewd conduct. Bartenders serving a drink to an undercover officer were sometimes arrested for soliciting sex or being in the employ of a bawdy house. Other charges randomly used were disorderly conduct and public indecency. If the false charges were met with the slightest protest, a charge of resisting arrest was added. Police cruisers sometimes parked outside LGBT bars with their lights flashing to intimidate and deter patrons. A crackdown on vice was a popular platform for politicians, so police harassment always escalated around election time.

The police rarely expected trumped up charges to be contested because those arrested usually wanted to pay their fine and extricate themselves from the situation as quickly as possible. But for increasing numbers of LGBT people, discrimination and harassment were no longer acceptable. We began to organize and our bars became political zones. Taking a cue from the anti-war and civil rights movements, and with an influx from the student movement — by the late 1960s we began to resist. Great lesbian attorneys like Rennie Hanover and Ralla Klepak joined the pioneering work of Pearl Hart in defending many of those who were unjustly arrested.

In 1968, police harassment escalated. Mayor Richard J. Daley was anxious to clean the city of vice before the Democratic National convention. After raids on Sam’s and The Annex, gay activists held a press conference denouncing the illegal raids and afterwards circulated a petition to muster public support. Pamphlets were distributed to bar patrons, explaining their rights if they were arrested. The homophile organization, Mattachine Midwest, with members like the late Bill Kelly and Marie Kuda, published news and commentary of recent bar raids.

Also in 1968 The Trip was raided – again through illegal means – when the community fought back, the charges were dropped. When the bar was raided again months later, the Liquor Commission took away The Trip’s license for “review” – when they did, the bar took the case and the License Appeal Commission of Chicago all the way to Illinois Supreme Court… and The Trip won.

In April of 1970 The Gay Liberation Front called for a one night boycott of the bars by having a Liberation Dance at the Coliseum Annex. The group had a list of demands for bar owners including same sex dancing and no gender dress rules. Two thousand people attended the Coliseum dance. The next weekend gay activists picketed outside the Normandy Inn, drastically cutting into the bar’s business. Activists were protesting for the right to dance. Not long after that, The Normandy Inn became the first Chicago gay bar to allow same sex dancing.

Through these cases we became empowered. We saw that we could win and that activism brought results. Two months later Chicago had its first Gay Pride Parade and we were off and running.

Our bar-based activism eventually led to recognizing community needs and taking steps to address them. Much of this was done through bar networking and fundraising. In 1974, in response to our community’s increased “social activity,” Howard Brown Clinic was founded as a VD clinic and even had a VD Van that would park on the street near the gay hot spots on Saturday nights to offer free STD testing. In the late 1970s, The Gay Athletic Association grew out of the bars, and was made possible through bar sponsorship.

Our bars also fostered and supported talent. LGBT specific music and comedy blossomed through open mics and talent nights. Other LGBT friendly acts found work in the developing circuit tours of gay bars and bathhouses, a booking tour jokingly referred to at the time as the “KY Circuit.”

The emotional connection provided by the bar community was vital as well. Gay bars often had Thanksgiving or Christmas dinners for those without biological families, because in the process of all this, we had become a family.

This connectedness and sense of community was expansive. We began to see ourselves as a part of a larger LGBT community – what affected LGBT people in Atlanta or Dallas or San Francisco affected us, too. A prime example of that grander camaraderie was the response to Anita Bryant’s “Save our Children” campaign in 1977. Bryant effectively used her modest celebrity as Orange Juice Industry spokesperson and former Miss Oklahoma to attack an ordinance in Dade County, Florida, which extended basic civil rights protections to homosexuals. By fanning public hysteria at the notion of gay teachers, Bryant successfully got the county board to overturn that anti-discrimination measure. Due to networking here in Chicago, largely coordinated through our bars, over 5,000 marchers turned out to protest Bryant’s appearance at Medinah Temple; the subsequent Orange Ball dance raised over $10,000 to combat Bryant’s homophobic measures.

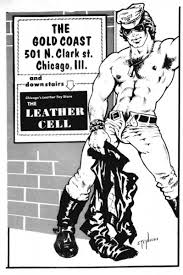

Once we began to claim our visibility and strength, we never relented. Huge non-political events began to emerge that required extensive communication and cooperation nationwide and globally. The International Mr. Leather contest and the Miss Continental franchises had their starts at The Gold Coast and The Baton and remain Chicago based.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were an incredible era for Chicago bars and clubs with places like The Bistro, The Gold Coast, Carol’s Speakeasy, and The Redoubt to name a fraction of the nightspots. Our neighborhoods were the place to party. This period was defined by a revelry in our new freedoms and joy of the moment. And it also featured a soundtrack meant for dancing. We had escaped our previous social constraints, cast aside many social taboos, and embraced the era’s hedonism with a vengeance. The celebratory nature brought us even closer as a tribe.

The emergence of our bars as socializing as well as organizing spaces, and the blending of those two functions cannot be underestimated. Without that profound marriage of kinship and activism it’s doubtful we would have survived our greatest challenge: the AIDS crisis.

During the earliest days of the epidemic our bars routinely distributed condoms and disseminated safe sex information because that life-saving education was being actively denied by the government and the mainstream media, which had become obsessed with marginalizing those seen as most vulnerable to the virus.

Howard Brown’s STD testing began to shift from basic STDs to HIV testing and the eventual treatment of AIDS patients. Planning for the creation of Chicago House, an AIDS living and care facility, began in meetings at the Baton and in the back of Big Reds. As need arose so did the number of organizations — Open Hand, AIDS Legal Council, Test Positive Aware Network, Act-Up, Stop AIDs, Kupona Network. These and many other AIDS organizations emerged and were primarily funded through community efforts. Door collections were welcome at nearly every Chicago LGBT bar and club; and most every LGBT bar hosted countless fundraisers to accommodate the myriad of needs prompted by the epidemic.

Though our community was decimated by AIDS, we survived the worst of it. Instead of destroying us, we emerged stronger, learning through sheer necessity how to fight and organize as never before. We gained clout, we gained protections under the law, and we became the insiders. Today Chicago has no fewer than five openly LGBT elected representatives in the City Council – among the highest percentage of LGBT representation of any major city government. Politicians now have fundraisers in our bars and even if they vote against us, they still want to ride in our pride parade.

Our bars have had serious faults, often reflecting larger social prejudices and problems. Racism has been an issue, as evidenced by the protests over the door practices of some bars which required multiple IDs from People of Color. Other bars had a hat policy designed to discourage admittance of African-American patrons. The North Halsted Corridor – the business and cultural nexus of Chicago’s LGBT community – is still widely referred to as “Boystown” and seen by many as a predominantly gay white middle class area. Sexism has been an issue in the bar community and transphobia at other clubs and venues has been and continues to be commonplace.

In an era of hook-up APPS and LGBT mainstreaming some feel our bars have become passé or dated. I couldn’t disagree more. Last June our community was devastated over the Pulse Nightclub tragedy in Orlando. For many, that massacre had the same sort of jarring and intrusive impact as if the violence had occurred in a church or a synagogue or a mosque. For many there was also the recognition of vulnerability. We’ve all spent time in bars where any of us could be a victim of hatred by simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. But our response last June, to our feelings of fear and vulnerability, wasn’t to hide in isolation. Instead we came together, because coming together as a community has always been our cornerstone – it has been our strength and our reassurance, and that was a lesson we learned in our bars.

Coming together will be crucial in the days to come. If we are to survive this hostile administration and its noxious agenda we are going to have to unite once more and build coalitions with others under attack. Fortunately, we now have a history and we know it’s possible to survive challenging times if we face things together. Without unity, we may well return to the darkness of the closet and the criminalization of our existence.

I have no doubt that conversations about LGBT resistance and fighting back are happening right now all over the country and I’m sure that many of those activist conversations are probably happening in a gay bar.

コメント